Importance of HIV Testing

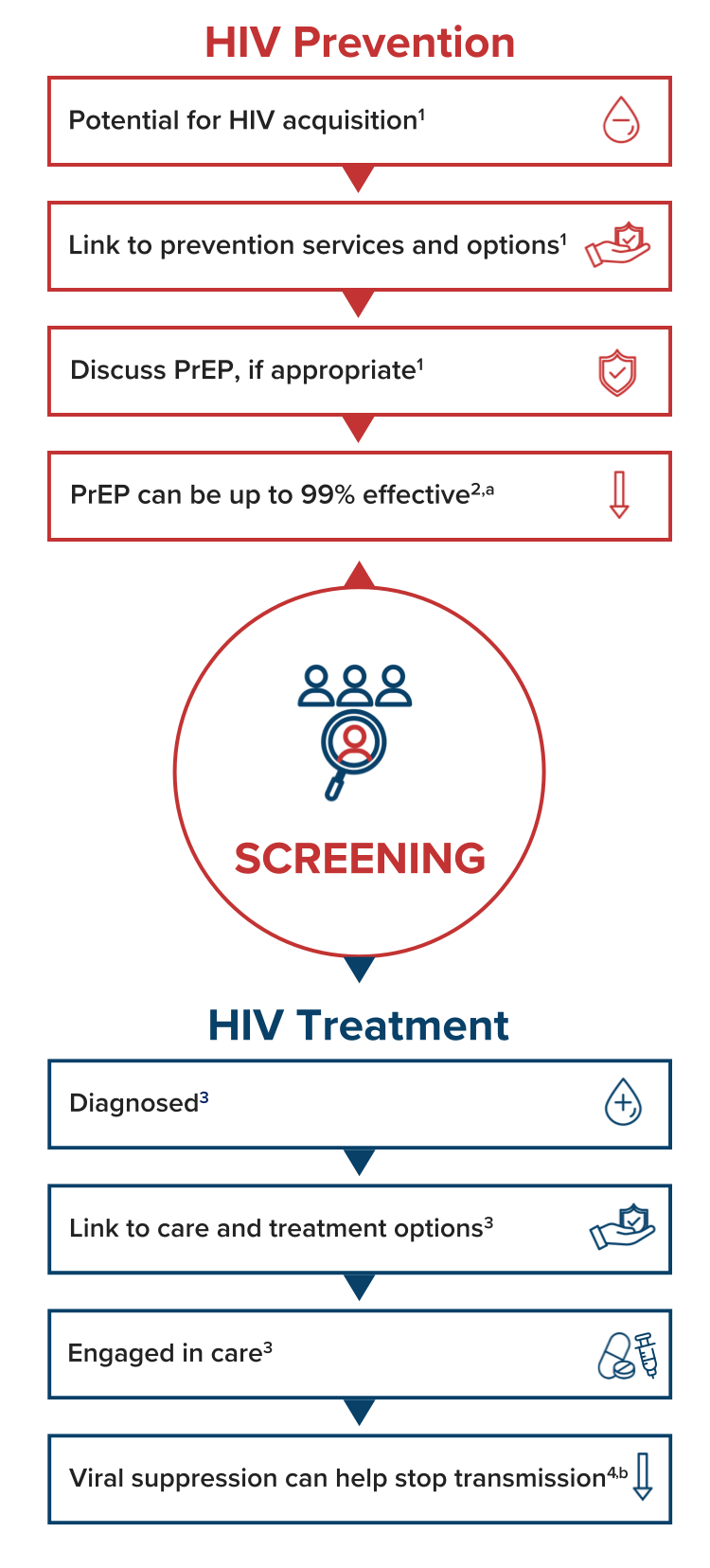

HIV Screening Is the First Step for Both Prevention and Treatment1

A status-neutral approach means taking action after every HIV test to either educate on HIV prevention or initiate effective HIV treatment.1 Each step provides an opportunity for collaborative conversations essential for engagement in care.

CDC Recommends1:

- All individuals aged between 13 and 64 years get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine healthcare

- Screen individuals who may have a higher likelihood for HIV acquisition at least annually

aWhen taken as prescribed, PrEP is only approved for prevention of HIV transmission through sex.

bAchieving and maintaining an undetectable viral load (<200 copies/mL) prevents HIV transmission through sex when taking antiretroviral therapy as prescribed.

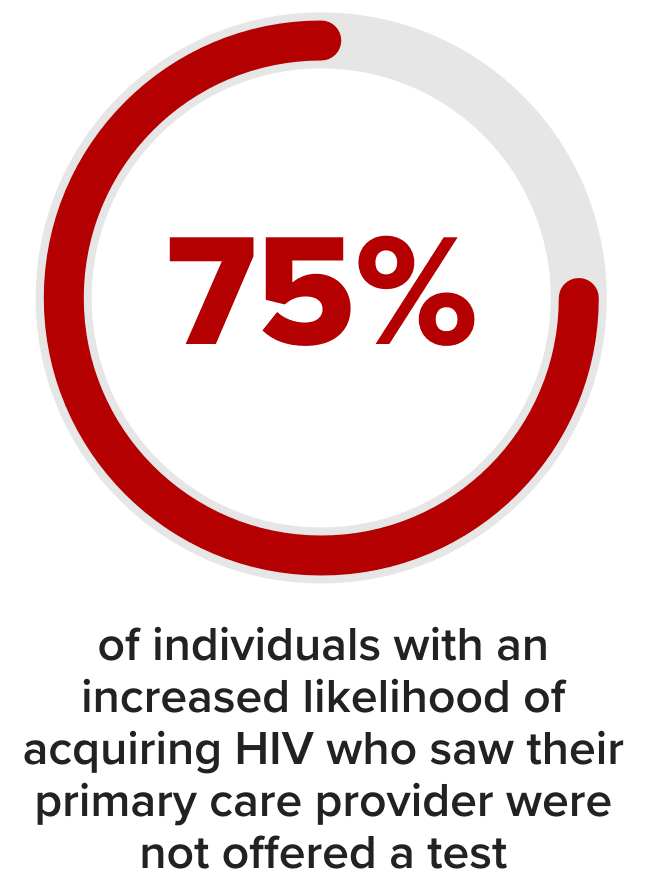

There are missed opportunities for HIV screening5

In a national survey conducted in 2021 (N=6,072), an estimated 72.5% of adults had never been tested for HIV.5

A separate study, conducted between 2014-2016 in people with higher likelihood of HIV acquisition found that many individuals were not screened.5,c

Integration of HIV testing in routine healthcare1,7:

- facilitates linkage to care and person-centered care

- transmits knowledge about testing to the broader community

- helps destigmatize HIV

- avoids missing potential candidates for HIV prevention services

HIV Testing Options8

| Rapid Point-of-Care | Standard Point-of-Care | Nucleic Acid Testd | At-Home Tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Antigens & antibodies | Antibodies | HIV RNA | Antibodies |

| Window Periode | 18-90 days | 23-90 days | 10-33 days | 23-90 days |

| Results | <20 minutes | 5-10 days | A few days | 20 minutes |

| Method | Finger prick | Blood draw | Blood draw | Swab |

| Rapid Point-of-Care | |

|---|---|

| Measures | Antigens & antibodies |

| Window Periode | 18-90 days |

| Results | <20 minutes |

| Method | Finger prick |

| Standard Point-of-Care | |

|---|---|

| Measures | Antibodies |

| Window Periode | 23-90 days |

| Results | 5-10 days |

| Method | Blood draw |

| Nucleic Acid Testd | |

|---|---|

| Measures | HIV RNA |

| Window Periode | 10-33 days |

| Results | A few days |

| Method | Blood draw |

| At-Home Tests | |

|---|---|

| Measures | Antibodies |

| Window Periode | 23-90 days |

| Results | 20 minutes |

| Method | Swab |

dFor people with potential exposure/early symptoms.

eThe window period for an HIV test refers to the time between HIV exposure and when a test can detect HIV in the body.

The CDC recommends that the HIV testing approach involves two steps9:

- Initial screening using an antigen-antibody test

- Follow-up testing of reactive samples with an HIV-1/2 antibody differentiation assay and/or nucleic acid test to confirm the diagnosis

MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people who inject drugs.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical testing guidance for HIV. Updated February 10, 2025. Accessed September 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/hivnexus/hcp/diagnosis-testing/index.html

- National Institutes of Health. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Updated July 3, 2025. Accessed September 5, 2025. https://hivinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv/fact-sheets/pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. HIV care continuum. Updated September 4, 2025. Accessed September 5, 2025. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/other-topics/hiv-aids-care-continuum

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical care of HIV. Updated February 10, 2025. Accessed September 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/hivnexus/hcp/clinical-care/index.html

- Dailey AF, Hoots BE, Hall HI, et al. Vital signs: human immunodeficiency virus testing and diagnosis delays — United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:1300–1306. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6647e1

- Patel SN, Emerson BP, Pitasi MA, et al. HIV testing preferences and characteristics of those who have never tested for HIV in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2023;50(3):175-179. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001746

- Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Integrating HIV Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive health care to avoid exacerbating disparities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1883-1889. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304061

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Getting tested for HIV. Updated February 11, 2025. Accessed September 18, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory testing for the diagnosis of HIV infection: updated recommendations. June 27, 2014. Accessed September 5, 2025. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/23447